Justicia Shipena

Seven years after its introduction, the National Equitable Economic Empowerment Framework (Neeef) remains incomplete, leaving Namibia’s ambition to tackle deep-rooted inequality hanging in the balance.

The framework, which has been under development since 2018 and aims to address the country’s persistent socioeconomic disparities and inequalities rooted in past discriminatory laws, has yet to be finalised.

Despite being described last week as “at an advanced stage” by the Law Reform and Development Commission (LRDC), Neeef has been stuck in development for years.

During a meeting with prime minister Elijah Ngurare, the LRDC said the framework is close to completion. Ngurare urged the commission to accelerate its finalisation and implementation.

The slow progress continues to raise questions about the government’s commitment to economic transformation.

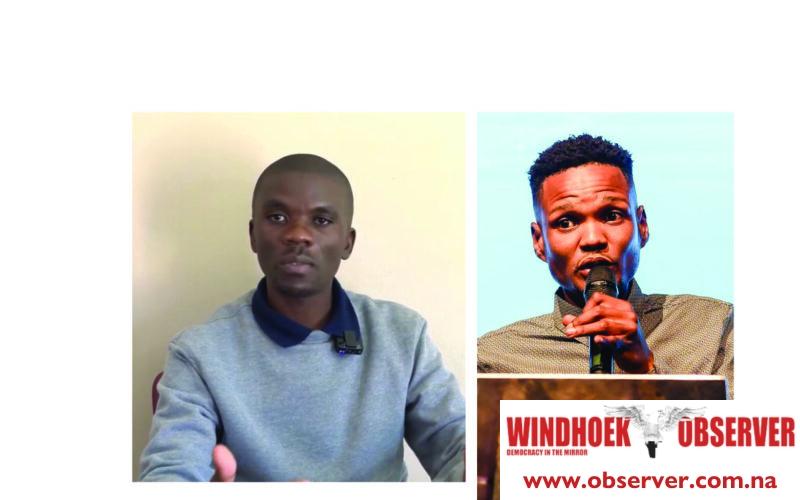

Social justice activist Lloyd Bock said the prolonged delay shows a lack of urgency in addressing inequality.

“When we look at youth unemployment, the economic crisis, and the lasting effects of apartheid, we must ask how serious the government is about balancing the playing field. Seven years is too long for a country of three million people facing such high unemployment. This policy could have already helped address some of these issues,” he said.

Bock said empowerment efforts should focus on the grassroots rather than benefiting those already economically privileged.

He noted that ownership in major companies remains concentrated in white hands.

“Most shareholders in companies are still white people, and this is exactly what the framework was meant to address. The slow pace shows how unserious we are about tackling these injustices,” he told the Windhoek Observer.

He also critiqued the consultation process, saying ordinary Namibians were not meaningfully involved in shaping the policy. Bock argued that Namibia lacks a proper public consultation policy, weakening public participation in national policy development.

Another activist, Julius Natangwe, echoed similar views, saying the delay casts doubt on the government’s seriousness about reducing economic disparities.

“While changes in administration may have contributed to delays, the continued absence of the framework reflects a lack of urgency in tackling deep-rooted injustices,” he said.

Call for wage disclosure law

Natangwe said wage transparency remains one of the most urgent reforms needed to address inequality.

“We need a law that compels employers to give employees access to payroll information. Many people doing the same job are paid differently, sometimes because they are women or because they are black or white. That does not help the process of closing the gap,” he said.

He said disparities are visible in both the private and public sectors, especially within financial institutions.

“Right now, salaries are treated as confidential, and even if someone finds out, they cannot raise it without being questioned about where they got the information. A payroll access law would change that,” he said.

Despite his criticism, Natangwe said there is hope that the new administration and parliament could accelerate progress.

“The new administration has not been in office for even a year, so maybe we should give them the benefit of the doubt. With a more energetic parliament, perhaps things will start to move,” he said.

Back in 2018, the Namibia Statistics Agency (NSA) revealed that over 70% of productive agricultural land remained in the hands of previously advantaged Namibians, mainly whites.

At the time, critics opposed the Neeef because of a clause requiring white-owned businesses to sell a 25% stake to previously disadvantaged black Namibians. The clause has since been scrapped.

The late president Hage Geingob in 2019 expressed disappointment that wealthy Namibians were reluctant to share with the poor to help address inequality.

He had said despite the government’s “softer and friendly approach” through initiatives such as Neef, hostility toward the policy persisted.

In 2018, the government reserved N$700 000 for its implementation.

Balancing empowerment and investment

Political analyst Sam Kauapirura stated that the government is currently grappling with striking a balance between promoting empowerment and upholding investor trust.

He said the current administration’s focus on foreign investment in oil and green hydrogen has made it cautious about empowerment measures that could be viewed as unfriendly to investors.

“I don’t really expect a serious commitment. That framework has gone through various reviews, and every time there seemed to be political will, questions around foreign direct investment came up. This government is driving the oil and clean hydrogen agenda, which is 100% foreign investment dependent and sensitive. So this framework would have to balance the interests, aspirations, and fears of those key industries,” he said.

Kauapirura said this tension explains the repeated delays.

“Every time the business community expresses fears and concerns, the grounds shift and amendments are suggested. Now, with these key industries of the future, those interests would have to be balanced,” he said.

He added that while the government may continue to promote transformation, local beneficiation, and local content, it is likely to water down ownership provisions.

It will probably emphasise training locals, employment equity, investment in emerging enterprises, and uplifting the SME sector. But the ownership pillar is expected to be watered down significantly for that legislation to survive,” he said.

“Improving equitable distribution of wealth in Namibia is crucial because high inequality hinders wealth creation for all, stifles long-term growth, and worsens the triple burden of poverty, unemployment, and inequality,” said economist Josef Sheehama.

Sheehama said Namibia needs coordinated policies that expand financial inclusion, create jobs, and strengthen education, while fighting corruption in order to attract investment.

He added that Namibia continues to rank among the most unequal countries in the world. In August last year, the Rand Merchant Bank ranked Namibia as the second most unequal country globally, with an inequality index score of 59.1. The World Bank also confirmed Namibia’s position as the second most unequal country in the world.

“To achieve economic equilibrium, wealth must include inheritance and asset income,” he said. He called on authorities to develop measurable indicators to track progress, including business ownership, workforce parity, and skills development. “It is not just a question of morality; it is an investment in the political, social, and economic prosperity of all Namibians,” Sheehama said.