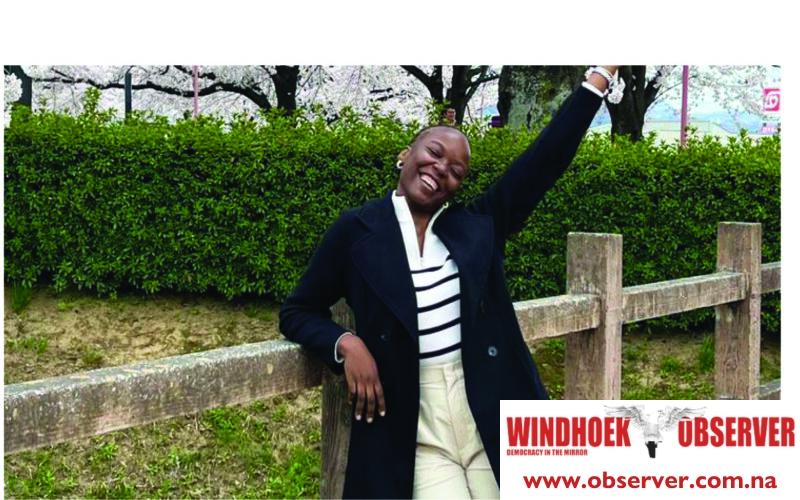

When most Namibians dream of life after graduation, their thoughts rarely drift as far as the bustling streets of Tokyo or the quiet countryside of Japan, but for Loide Mpinge, a young Namibian who studied education at the Hifikepunye Pohamba Campus in Ongwediva, the classroom has taken on a whole new meaning thousands of kilometres away.

Now living in Japan, she spends her days teaching English to Japanese learners beyond the rules of grammar and punctuation and also to speak and connect across cultures. Hers is a journey of courage, determination and the willingness to take a leap of faith. In this interview with the Young Observer, she shares the lessons Namibians can learn about taking opportunities abroad.

1. Tell us a little about yourself

My name is Loide Golden Mpinge. A 27-year-old lady, born and raised in Northern Namibia, from the dusty streets of Ongwediva. Growing up there was the best experience. Unlike many others, I never went away. At one point, I even moved deeper into the northern regions to complete my 10th grade at Omapopo Combined School, where my mother was the principal. After that, I attended Gabriel Taapopi High School and later studied at the Hifikepunye Pohamba Campus of UNAM, where I completed my degree in education with a focus on languages.

After graduation, I took a temporary teaching position at Natangwe Uugwanga Primary School for three years. It was an eye-opening experience under wonderful leadership and colleagues. Work didn’t feel like work because it was fun and challenging at the same time, but the environment was healthy, supportive, and incredibly rewarding.

2. Growing up in Northern Namibia, what were your dreams for the future? Did you ever imagine they would take you all the way to Japan?

Growing up in the north, I often watched people leave home to pursue careers or education elsewhere, and it planted a deep longing in me to one day do the same. I remember my cousin studying in China and coming back with what felt like a whole new energy and a fresh perspective that fascinated me. It made me curious about life beyond Namibia and what it would feel like to experience a completely different way of living.

Even though I stayed in Ongwediva for university and had Namibian friends, I had also become friends with students from countries like Malawi, Zambia, Zimbabwe and Botswana. I admired their courage to live outside their homelands and found myself quietly promising that I, too, would one day take that leap. I didn’t have a specific destination in mind, but I told myself that if I was still in Namibia by the age of 30, I would at least move to Cape Town.

Japan, however, was never part of the plan. It is what I like to call a beautiful accident. My initial dream was to teach in South Korea, but Namibia isn’t classified as an English-speaking country, which meant I couldn’t pursue teaching there. When I asked the agency assisting me with overseas job placements about other options, they suggested Japan. They said it was close to Korea and shared some cultural similarities (something I now know isn’t quite true), and I simply thought, “Why not?”

That decision opened the door to an incredible adventure. Japan became the perfect first step into life abroad. It is a place of safety, rich culture, and endless opportunities for growth. Looking back, I can honestly say it’s been the most wonderful introduction to living outside Namibia.

3. What inspired you to pursue education as a career?

To be completely honest, I can’t say that pursuing education was a calling I felt deep inside. It was more a path I found myself on. It was my mother’s influence that steered me in this direction. She dedicated her entire career to teaching, eventually rising to the level of school principal, and she recognised that I was a bit uncertain about my own future at the time. In her wisdom, she encouraged me to study education, believing it would give me a stable foundation. During those years of studying, I often felt like I was simply floating, taking each exam as it came without a grand plan in mind.

Nevertheless, out of respect for her guidance and maybe a little fear of telling a Kwambi mother otherwise, I followed that path. Looking back, what started as my mother’s decision became an unexpected gift, opening doors I never imagined and ultimately shaping the journey that led me all the way to Japan.

4. When did the idea of teaching abroad first become real for you, and what sparked it?

The idea of teaching abroad only truly became real for me when I was actually packing my bags to leave. It was at that moment that it hit me: this was really happening. Even upon arriving in Japan, I kept thinking, “There’s no way this is actually my life!” It was the preparations, the tangible steps, that made it feel real.

What sparked the journey, however, began much earlier. I had a friend who lived in Norway at the time, and I often told her about my own desire to leave Namibia. She told me about an agency she had used that helps teachers secure teaching positions abroad. They assist people with degrees in various fields, handling all the arrangements. Hearing about a reliable option sparked confidence in me, as I preferred paying for convenience rather than risking mistakes or scams.

The process of securing a permanent teaching post in Namibia is extremely rigorous and highly competitive. You would assume that having a degree qualifies you to teach English, but the system says otherwise. The interviews are endless and fiercely competitive, with hundreds of candidates travelling from across the country just for a chance to be the one selected, sometimes out of 500 applicants. Considering this, I thought, ‘If my chances are better and I am almost certain to get a teaching job elsewhere, without all the endless document memorisation and competition, and with the added benefit of seeing the world and experiencing teaching in another country, why not take that path instead?’

So I reached out to the agency, shared my expectations, and they presented my options. With their support (and, of course, a fee), everything started falling into place. The idea had always been there from a young age—the longing to see the world and live abroad—but this was the moment it manifested into reality.

Another factor that encouraged me to take the leap was my temporary teaching post back home. Even when a permanent English teaching position became available at my school, the timing was off; I had already started preparations to leave. I realised my window of opportunity in Namibia was limited, and pursuing an overseas teaching position was the best option.

Ultimately, it was a mix of lifelong curiosity, opportunity, timing, and the desire for certainty. I love to travel, and this was a chance to explore the world while continuing my now-developed passion for teaching. It felt like the right moment to take a leap of faith, and I’m grateful that I did.

5. How did your time studying education in Namibia prepare you for stepping into a classroom on the other side of the world?

I’d like to think that my time studying education in Namibia provided a solid foundation, but what truly prepared me for teaching abroad was the hands-on experience I gained during my three years as a teacher in Namibia. That time helped me identify both my strengths and areas for growth as an educator.

Interestingly, I’ve noticed that students in Namibia often have stronger English skills than students in Japan, since English is a second language back home, whereas here it is taught as a foreign language. I spent my time teaching in a village at Natangwe Uwanga School, and looking back, I wish I could go back and applaud those students rather than strictly focusing on their mistakes. That experience taught me that education doesn’t have to be rigid, and it can be complex, interactive, and fun.

One thing I’ve observed is that in Namibia, teaching can sometimes lack passion, partly because student development is not always supported collectively by families, communities, and schools. When children don’t receive holistic guidance from home and society, it makes teaching more challenging, and it can dampen a teacher’s enthusiasm.

In Japan, I’ve seen a striking contrast. The students are fully supported not just by teachers but by their parents and community, which creates an immersive and wholesome learning experience. It’s inspiring to see how this collective effort allows students to enjoy learning and develop confidence in their skills. My experience in Namibia prepared me as best it could, but living and teaching here has taught me new perspectives on education, passion, and the power of community involvement in shaping successful learners.

6. Can you take us through the process of getting to Japan? (Recruitment, VISA and Travel)

The process of getting to Japan was surprisingly smooth, especially with the support of the agency representing me. The initial screening required me to submit basic documents, such as my CV, degree certificates, and a valid passport. After that, I was asked to create a short video to demonstrate my English proficiency and a demo lesson, where I pretended to teach a classroom. This allowed them to see how I would interact with students and manage a lesson.

Once that stage was complete, the agency coordinated with schools in Japan to find a placement that matched their needs. The next step was an interview with a representative, where I was asked about my teaching experience, my motivation for coming to Japan, what I knew about the country, and my long-term goals. Passing the interview meant they could finalise my placement and let me know the region where I would be based.

After the placement was confirmed, the agency provided me with a Certificate of Eligibility (COE), which I submitted to the Japanese Embassy in Namibia to obtain my VISA. The visa process itself was very fast—my visa was ready the very next day after submitting all the documents.

Overall, the process can be completed within six months, as long as you have the necessary documents, funds to pay the agency and enough money to cover initial living expenses in Japan. Having the agency handle most of the steps made everything straightforward, and it gave me peace of mind knowing that my move would go smoothly.

7. Is there something in Japan that you wish Namibia could adopt, maybe in terms of culture, technology or lifestyle?

There are many things in Japan that I admire, but if I were to highlight three aspects that I wish Namibia could adopt, they would be safety, social welfare, and responsibility.

First, safety. Living in Japan has been a remarkable experience in terms of security. I can walk around freely, even at 3 a.m., without worrying about my belongings or personal safety. I don’t even remember the last time I locked my apartment, yet everything is always in place when I return. Experiencing this level of calm and security in a foreign country is both comforting and humbling.

Second, social welfare. Namibia has a population of just over three million, yet we face challenges in feeding and caring for everyone adequately. In Japan, despite a population exceeding 100 million, I have not seen beggars on the streets. The government ensures that citizens are provided for, which in turn helps mitigate crime. Witnessing such effective social support has been eye-opening, and I dream of a Namibia where every citizen’s basic needs are met, creating a foundation for a safer, more stable society.

Third, responsibility and work ethic. People in Japan take their roles seriously, whether in the workplace, school, or community. Everyone knows what is expected of them and strives to meet those expectations. The culture emphasises punctuality, dedication, and going the extra mile. If Namibia could embrace a similar culture of responsibility and accountability—where citizens and institutions work diligently to serve one another—we could reach new heights, especially given our small population.

Therefore, these three aspects – safety, social welfare, and responsibility – have left a profound impression on me. While I recognise that cultural and systemic changes are not easy, I believe that Namibia has the potential to adopt these practices and create a stronger, more thriving society.

8. What do you miss most about Namibia while living in Japan?

What I miss most about Namibia is, without a doubt, the food. Especially biltong, pap, and boerewors. I never realised how much these flavours were a part of my daily life until I was away, and while I’ve learnt to adapt, there’s a part of me that still longs for the taste of home.

Even more than the food, I deeply miss my family—the warmth, comfort, and sense of belonging that comes from living in my mother’s house without the pressures of bills or responsibilities. I miss the hugs, the laughter, and simply being surrounded by people who love and understand me. The comfort of home, family, friends, and familiar flavours is something that no matter where I go, I will always carry with me in my heart.

9. How different is everyday life in Japan compared to Namibia?

Living in Japan has made me realise that, at the core, everyday life isn’t so different from home. Everyone wakes up, goes to work, fulfils their responsibilities, returns home and carries on with their routines, whether that’s cooking dinner, going to the gym or pursuing other personal activities. Life is essentially life, no matter where you are.

For me, this realisation has inspired me to create a life that I enjoy and feel productive in. I’ve picked up a walking routine, although not every day, but whenever I feel motivated because it’s good for my body and helps me take a break from my phone. I also record TikTok videos to capture unique experiences, especially moments I wouldn’t have in Namibia.

Being in a country where the language is not my own means I often spend a lot of time on my own, which could feel dull if left unchecked. To counter that, I’ve pursued hobbies I love, such as practising makeup and learning to cook new meals with the help of TikTok. I challenge myself to learn new skills or improve on ones I’ve already started to develop.

Ultimately, I’ve carved out a little life for myself here, one that I’m comfortable with and happy in. It’s not complicated, and it has taught me that everyone is just doing life in the best way they know how. I’ve found my own rhythm abroad and discovered a little piece of life that’s truly mine.